Media Coverage

Gullah Society, protector of Black burial grounds, dissolves, but its ‘work can continue’

preservation-admin , August 18, 2021

Read the original Post and Courier article here

The Gullah Society, a nonprofit founded by the late Ade Ofunniyin that sought to document and protect Black cemeteries in the region, has been dissolved by its governing board.

The organization operated on a shoestring, relying on volunteer researchers and strategic partnerships, but under Ofunniyin’s determined leadership it succeeded in identifying and cataloguing dozens of cemeteries and burial grounds throughout Charleston and beyond. It raised awareness of a long-standing problem: how real estate development and the forces of change threaten the sacred resting places of the dead.

The Gullah Society began as a project of the heart, but it became a formal organization around the time the remains of 36 Africans were discovered in 2013 during the renovation of the Gaillard Center. Since then, The Gullah Society has worked to describe and secure several sites, from the Charleston Historic District to Cainhoy.

These efforts are ongoing, and some of the people who have been affiliated with the group will continue the work of documenting the graveyards and advocating for their protection.

Ofunniyin died on Oct. 7 after suffering an acute health crisis. He was the grandson of famed blacksmith Philip Simmons and had family roots on Daniel Island. Ofunniyin earned a Ph.D. in archaeology and spent significant time abroad where he studied the cultural and religious connections between West Africans and African Americans.

He taught at the College of Charleston, and he led the effort to reinter and honor the enslaved people whose remains had been discovered near the Gaillard Center. After his unexpected death last year, his organization was left rudderless, with no permanent headquarters and few assets.

Board President Johanna Martin-Carrington, 90, confirmed that the paperwork has been submitted to the S.C. Secretary of State’s office to dissolve The Gullah Society, but she said she hopes others will carry on its mission.

“It’s gone in name, but the work can continue,” she said.

Without Ofunniyin — his energy, ideas and commitment — it has become too difficult to sustain the organization, she said.

Grant Mishoe, the group’s main researcher, said the core team continues to function under the auspices of the Anson Street African Burial Ground Project and the African American Cemeteries Restoration Project.

The former continues to examine the DNA of the remains found at the Gaillard thanks to grant funding from the National Geographic Society. The latter continues to investigate the details of nearly lost cemeteries on the Charleston peninsula with support provided by the Preservation Society of Charleston, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the city of Charleston and the International African American Museum.

Charleston officials presented a new cemetery ordinance on Aug. 17, which City Council passed unanimously on first reading. The ordinance, partly inspired by the work of Ofunniyin and the Gullah Society, would empower the city to intervene when gravesites, known or suspected, are at risk from “ground disturbing activity.”

“It is unlawful for a person to destruct or desecrate a burial ground where human skeletal remains are buried, a grave, graveyard, tomb, mausoleum, or other repository of human remains without property legal authority,” the ordinance states. “It is unlawful for a person to desecrate a gravestone, memorial monument, marker, park or area commemorating a deceased person or group of persons.”

When adopted, the ordinance will enable the city to issue a stop-work order, to administer oversight and to penalize those who do not adhere to the rules.

Robert Summerfield, the city’s director of Planning, Preservation and Sustainability, said the ordinance was badly needed.

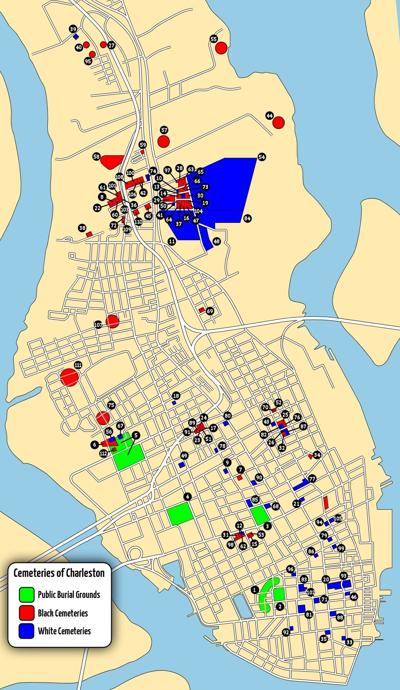

A map of Charleston’s many cemeteries and burial grounds, created by Grant Mishoe of The Gullah Society. Grant Mishoe/Provided Grant Mishoe/Provided

“Up ’till now, the city had nothing regarding protection, especially of gravesites outside a cemetery,” he said.

State law criminalizes defacement and damage of burial grounds, and the state Department of Health and Environmental Control has jurisdiction over gravesites, though its enforcement capabilities are limited. Charleston officials have made some effort to safeguard historic cemeteries, but have lacked the muscle a formal ordinance provides.

The new ordinance is a good start, but not enough, Summerfield said. What’s needed is a central repository of information on known or suspected burial sites that property owners and builders can access before they begin work.

Summerfield said he hopes the Preservation Society can help provide such information in the form of data sets that are integrated into the city’s GIS system.

“So this is a stop-gap,” he said of the new rules.

And it is distinct from an archaeological ordinance that could soon come before City Council after more than two years in limbo, Summerfield said.

Kristopher King, executive director of the Preservation Society, said his organization supports both ordinances, though harbors some concerns. He said he’s glad that protection of burial grounds, an urgent matter involving human remains, and the science of archaeology are being treated separately.

Director of Advocacy Brian Turner said he has investigated how other municipalities have dealt with these preservation issues.

“Generally, they share two things in common,” he said. “They base their planning decision on an inventory or map, and … an expert body tasked by the city provides landowners with guidance, or a process, if their property is on a known burial ground.”

That’s not part of Charleston’s approach, at least not yet, he noted.

“The proactive approach is missing,” Turner said. “On the other hand, this would get the city in the room” — and that’s essential given recent examples of gravesite disturbances such as those at 88 Smith St. in downtown Charleston and the Oak Bluff subdivision in Cainhoy.

In 2010, the Columbia-based Chicora Foundation produced a big study of burial grounds in the Charleston area called “The Silence of the Dead: Giving Charleston Cemeteries a Voice.” Since then, Mishoe and others have added more details. So there’s a basis for a central database anyone ostensibly could access, Turner and King said.

“We just have to make sure that this (cemetery ordinance) is not the end of the conversation,” King said.

That conversation was started in earnest by Ofunniyin, and it’s critically important if local burial grounds are to be preserved, King added.

“We need to ensure that all of his students, and all of the people he touched, pick this mantle up and continue this work.”

Stay up to date on PSC news by subscribing to our newsletter.