Media Coverage

Charleston architectural review changes would make some historic renovations less costly

preservation-admin , October 19, 2022

Read the original Post and Courier article here.

When Sarah Derrington bought her Wagener Terrace house in April 2020, she knew she had her work cut out for her.

“It was a total gut renovation,” she said.

But what she did not expect was that some of the repair costs she budgeted for could more than triple due to Charleston’s strict historic preservation standards.

All the windows on her 1945 home, 20 wood frame and 9 metal frame, were in a state of decay. Derrington anticipated it could cost her up to $30,000 to replace them.

She requested approval from the Charleston Board of Architectural Review to put in new ones. Her application was denied. Instead, the board determined that the windows needed to be restored.

When she got a quote from a company that specialized in historic restoration, she said she was shocked. Refurbishing the wood-frame windows alone would cost her $82,000. Restoring the metal-frame windows as well would have brought her costs close to $100,000.

“Obviously, this was way out of budget,” she said. “This is a house in Wagener Terrace. It’s not even South of Broad.”

Now, newly proposed changes to the Board of Architectural Review’s policies may make situations like Derrington’s less common.

The BAR process

Anyone who wants to make renovations to a building on the Charleston peninsula that is more than 50 years old, now from 1971 and earlier, must present those changes to the Board of Architectural Review. The board, which is divided into two committees for small and large-scale projects, is made up of volunteers with backgrounds in planning, historic preservation and architecture who are appointed by the mayor and City Council.

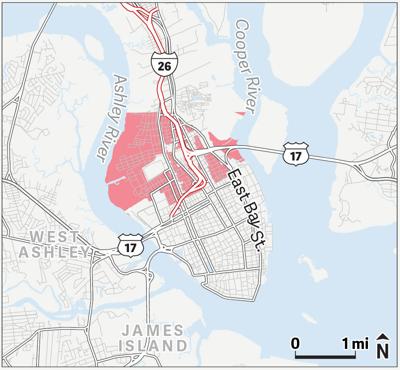

NORTH OF LINE POLICY CHANGES: Charleston is considering changes to the board of architecture review process for historic homes north of Line Street. They will add flexibility based on income and length of residence. (SOURCE: ESRI)

Brandon Lockett/Staff

While historic buildings are subject to varying preservation standards depending on their location in the city, those standards do little to differentiate between the economic realities of the homeowners. A new set of policy changes for buildings north of Line Street, which is a historically working-class but gentrifying area, aim to make the BAR process more accessible.

If approved by both BAR committees later this month, the policy changes will include more flexibility for those making 80 percent or less of the area median income (about $45,000 for a single person) and for those who have lived in their home for 25 years or more. The changes would also allow the BAR to offer suggestions for pre-approved replacement materials rather than denying replacement requests altogether.

“This will be the first time in our policies that we are addressing equity questions and creating some allowance for a legacy homeowner or someone who maybe has some financial obstacles,” said Robert Summerfield, the city’s planning director.

The policy would also allow city staff to review and approve most plans rather than requiring the homeowner to present plans to the BAR, which meets twice each month.

Even with loosened restrictions, the proposals keep some guardrails in place for buildings that are included in the National Register of Historic Places.

“I’m not anti-preservation or pro-dismantling the BAR. I think we need BAR to preserve our history,” said City Councilman Jason Sakran, who drafted the proposed changes. “But the current policy has been detrimental for the overall mission and goal of the board.”

Why north of Line?

The area of the peninsula north of Line Street was included as its own district under the BAR’s oversight as a way to protect existing historic homes in the once majority-working class neighborhood without being overly restrictive.

The opposite happened. BAR oversight north of Line follows a black-and-white set of standards. Changes to homes are approved or denied based purely on whether a historic aspect of a home, such as windows or a roof, will be repaired or replaced. Board members are not permitted to ask what a homeowner’s plans are to replace a certain element or provide suggestions for what materials that person can use to maintain the historic character of the home.

As a result, if a homeowner can’t demonstrate clearly why a replacement is necessary over a repair, the board may err on the side of caution and reject the application.

“Without being able to legitimately ask those questions and know what the replacement looks like, it didn’t provide the board a level of flexibility to exercise discretion, which is the point of having a board in the first place,” Summerfield said.

After feeling disheartened by the rejection of her request to replace her windows, Derrington said she decided to roll up her sleeves and restore the windows herself.

“The only thing to do for a normal person was to do the work yourself, or to live with rotten windows,” she said.

Derrington paid a trained preservationist $15,000 to oversee her work. She then took out the windows one by one and got to work.

With limited DIY-experience, she carefully removed the frames, many of which were crumbling, and used a blow torch to release the glass. She used a mix of wood filler and epoxy to shore up the frames. Then, she measured every pane of glass that hadn’t broken, many of which differed from each other by 1/16th of an inch, so that she could buy the correct size replacement panes. The glass panes cost her $10,000.

Often wearing a respirator, she sanded, primed and painted the frames, among other fixes. About three months after starting, she was finally able to put in the new panes of glass and rehang the windows. She also hired some specialists to help with the metal windows, costing her another $17,000.

Altogether, she spent over $40,000. While it was more than what she had budgeted, it was still half of what she would have paid for professionals to do the project from start to finish.

“Most people aren’t going to be able to do what I did. I turned my whole house into a workshop,” she said. “There was plastic all over the floor. I was exposed to lead paint. … We have to make it possible to preserve history in a way that’s reasonable.”

Rejected applications have led others to pursue more desperate measures. In July, WCBD-TV reported that a homeowner on Tram Court in the North Central neighborhood of Charleston was caught trying to tear down her own home with a rope tied to a pickup truck because her demolition requests had been repeatedly denied by the BAR.

Long-term goals

If implemented, the BAR policy changes could prevent some homes from falling into a state of disrepair as costly renovations add up, said Cashion Drolet, chief advocacy officer for the Historic Charleston Foundation. The foundation is supportive of the policy changes overall.

“I think a lot of people may have been deterred by the ambiguity of the (BAR) process and the perceived costs,” Drolet said.

The policy can’t, however, address issues with heirs’ properties, she added.

That’s when the person named on the deed isn’t alive, the potential claims of heirs have not been sorted out and a cascade of legal woes that threaten homeownership can follow. It happens when properties don’t go through the legal process known as probate, and it’s worse if the deceased owner didn’t leave a will. Without clear ownership, it’s not possible to get a mortgage, or home insurance or access to government home-repair programs.

Some dilapidated structures on the peninsula can be attributed to heirs’ property issues, but others may have been saved if restoration had been a more accessible, Drolet said.

“This will help make the BAR process more accessible to everybody,” she said.

The Historic Charleston Foundation and the Preservation Society of Charleston teamed up this summer to study the issue. Out of 98 requests to the BAR since 2017 to replace parts of historic homes north of Line, 66 were rejected. Out of those rejections, 70 percent were from individual homeowners and 30 percent were from investor-backed projects.

“There is a disparity between the average homeowner and these investor-backed projects, which have disproportionate success,” said Sam Spence, director of Public Affairs for the Preservation Society of Charleston.

He said the Preservation Society supports the policy change because it is strong enough to maintain a building’s historic character but flexible enough to make the process more accessible.